I admit to being a grump about AI. Not a pessimist so much as a skeptic, convinced that all the fuss on both sides amounts to either contagious boosterism or a moral panic, and that the innovations powering MidJourney are no more likely to lead to the end of the human race—or its apotheosis—than photoshop did. Or film photography for that matter. It’s just new tech, not a new world.

Don’t get me wrong: artificial intelligence in theory is alluring. It’s just that the technology being marketed as such right now is misnamed. Remember the hoverboard craze? They’re essentially Segway scooters without the handles but the company settled on hoverboard as a name despite the fact that there was already a consensus definition for what that was—a skateboard deck floating on air, as seen in Back to the Future II or any number of other sci-fi tales. But since making an actual floating skateboard is hard, perhaps even, given what we know about physics, impossible, they instead made this other thing that was kind of neat but not at all what the word hoverboard was intended to convey—and we all just kind of shrugged and let it slide because really, it’s not that important.

Except occasionally it is that important. Being a writer entails believing that names matter, that it isn’t pedantry to note that words smuggle connotations; that, however explicitly they are defined, they have a history, a culture, a life. And the life of the words artificial intelligence is replete with fantasy and melodrama. It’s Hal and the pod bay doors, it’s Arnold learning to love little Edward Furlong, it’s the Three Laws of Robotics, like incantations to ward off a destructive spell. It’s the idea that we can create a thing that rivals us, that understands us, perhaps even better than we do ourselves. It’s a remedy for the sad fact that we can’t teach more than a few hundred words of our language—any of our languages—to another sentient being. It’s a way of hoping we might not be alone.

It’s a beautiful dream—slightly terrifying, like all beautiful things should be—and it’s hard to fault anyone for chasing it. The problem is that, like floating skateboards, there no reason to assume that it’s actually possible.

We think of the brain as a computer, and we have some reason to believe that this is slightly more accurate than past analogies like telegraphs and water clocks. We know that information is being encoded somehow by the wet rhythms of our pulsing synapses, we know which areas of the brain are processing what types of information, but we don’t know how all of this adds up to the substance of thought, how that charged sluice of chemicals gives rise to something that we would recognize as a mind, capable of forming and acting upon representations of the world. The AI optimists believes that it’s simply a matter of processing power, that given enough data to crunch a mind will emerge—but they’re taking that on faith, and against evidence to the contrary. AI can play chess, solve dense mathematical problems, write novels (more on that later)—an elephant can’t do any of that, but it can recognize and mourn its dead. No reasonable definition of intelligence could prioritize the former over the latter. There’s more to a mind than math.

The technology currently being marketed as artificial intelligence—the engine driving the little powered by AI moniker that has suddenly shown up on every product from search engines to diet apps—is technically called Generative AI, distinguishable from Artificial General Intelligence, which is reserved for the as-yet-unrealized-and-quite-possibly-unrealizable version of AI we might recognize from fiction. If you’re paying attention you probably know this but the thing is most people aren’t paying attention (and no one can pay attention to everything) so when so many companies say they are making use of artificial intelligence the public will naturally assume that we are much, much closer to creating sentient synthetic minds than we actually are. There’s no consensus that the generative AI approach—crunching insanely large amounts of data (at equally insanely large energy costs) to generate statistically probable outputs—will lead to an artificial intelligence worthy of the name. Anyone claiming otherwise is either falling for the bait or setting the hook.

And if we can’t get the sentient companions of science fiction what are we left with? Useful automatons, like bodies reanimated not into Frankenstein’s introspective monster but into zombies, capable of navigating the input and output of the world but without a glimmer of understanding. ChatGTP is the man in the Chinese Room, spitting out correct answers without knowing what an answer is, what it means to be correct or incorrect, what it means to mean. It isn’t intelligent, it just does a pretty good impression.

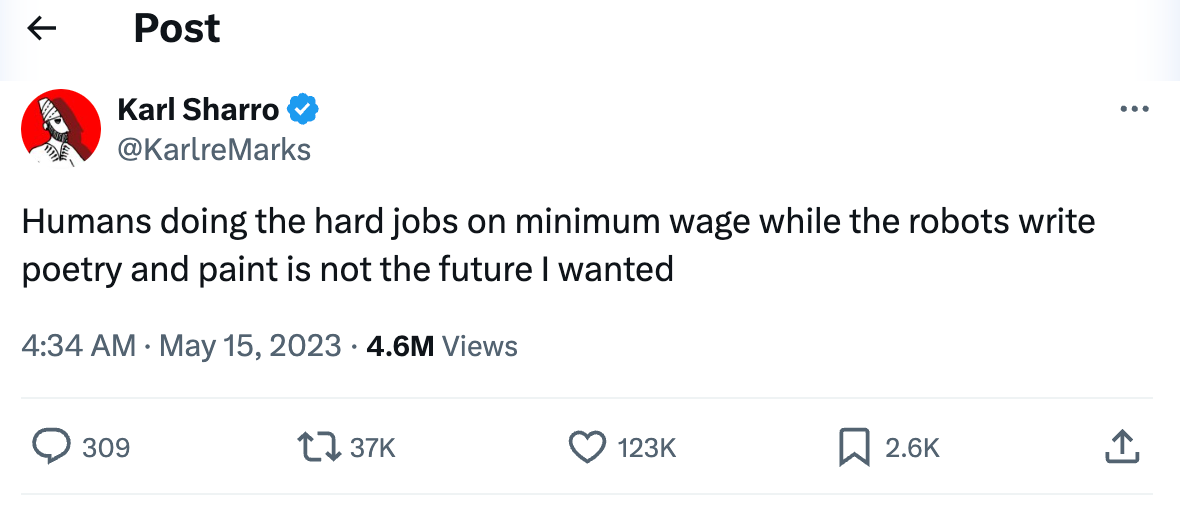

The risks imposed by this sort of technology aren’t metaphysical or existential—they’re far more mundane, indistinguishable from the risks posed by every new technology since at least the invention of agriculture, if not before: the decimation of certain forms of skilled labor.

Which forms exactly? Well, perhaps not the ones we expected.

Maybe we should have seen it coming. The desire for creative expression is a universal impulse, not limited to those with the drive or ability to indulge it. A common responses I get when people find out I’m an author is the confession that they too would like to write a book—a memoir, a novel, or a mashup of the two. Their ideas often sound interesting—many people have lived interesting lives, or have interesting stories to tell—but the barrier is always the execution. It’s the doing of the thing that gives them pause. So too with painting or making music. It’s a sad truth that creative talent—like all talent—is not dolled out in ways that are democratic or fair. Kids are born with potential but without opportunities, or with means but no potential. I love music nearly as much as I love to read but I couldn’t carry the tune to Happy Birthday if I had a hundred chances and my life was at stake.

Generative AI is seen by its boosters as a partial remedy to this dilemma. Do you love visual art but never learned to draw? Just tell the program what you want to see. Want to tell a story but can’t get the words to come? Type in a summary and your robot friend will do the hard stuff. The problem, though—and I’m hardly the first to point this out—is that the work, the process, is part of what makes the thing worthwhile. Wrestling with the blank page is a necessary step, not only for its relationship to the pleasure of doing the work, but to the quality of the final piece. Art exists in the shadowy spaces just outside the explicable. You want it to be one plus one equals two but it isn’t. You want a predicable result when you combine skill with labor but nothing could be further from the truth. No one writes the book they set out to write. For AI art in any form—text, visual, or sound—to be worthwhile it has to wrestle with its essential nature—the plagiarism, the misinformation, the dicey ethics of bodily representation, its dumb pastiche of understanding, its capacity to spit back something that is almost but not quite you—in formal ways, in the presentation and shape of the final piece. It has to be an integral part of the testing and probing, it has to become an element of the strain, not a way to alleviate it. It has to be more than touching up the edges of a rough draft spat out by ChatGPT.

But of course it is possible to write stories and books by simply touching up the edges of a rough draft spat out by ChatGPT. Students at all levels, to the frustration of their teachers, are doing it in droves. Amazon’s self publishing arm is littered with novels created in just such a fashion, the kind that in their word-salad specificity—paranormal cozy fantasy, or billionaire cowboy romance—are already so proscribed that the author’s job is little more then to fill in the interstitials between the required tropes. The most successful churn out a new book every couple of months; their thinness both enables their creation and is a source of their appeal. They’re not meant to be read as texts but absorbed as content; they aren’t competing with Tolstoy or Toni Morrison or even Stephen King, they’re competing with podcasts and TikTok. Speed is paramount. Take too long to make the next one and the writer risks losing their readers to someone else, the way you might abandon a link that is taking too long to load. Using ChatGPT or Sudowrite to maintain this blistering pace only makes sense. It’s the kind of task—iterative recombinations masquerading as novelty—that the tech is fine tuned for.

In many ways these writers are throwbacks to the pulp era—even if they are writing for very different demographics—and it’s a pulp era word that best describes them, an often-pejorative label that, in a culture allergic to the suggestion that some activities or projects might in any way be inferior to others, has fallen out of use: they’re hacks.

A hack writes for money. Not for love of the craft, not from a romanticized, yearning need to express themself (although they may have that)—but for the hard nuts and bolts of paying bills. Hacks write to eat. Hacks write 2 million words a year. Tell a hack at 8 pm to write a 5500 word short story and they’ll have finished copy on your desk in the morning. Hacks can sit in bookstore windows and turn the premises of strangers into fiction while you wait. Hacks produce.

Hack has commonly been used as an insult, an elitist sneer, but like all words—like AI, like hoverboard—it’s not a fixed term. Donald E Westlake called himself a hack, and based solely on his prodigious output it’d be hard to argue with him—but his best books are well-crafted marvels, so full of vivid description and sly, efficient characterization that you could use them as teaching texts in a creative writing class. Hack is most often associated with the pulps but it isn’t about genre, or about quality, it’s about intention. (It’s also, to a degree, about class. This is one reason Westlake and others adopted it for their own, to mark their solidarity with labor. To be a hack was to claim writing for the common man, to make books the way a machinist turned screws.)

Not all writers of commercial fiction are hacks. James Patterson is one—he doesn’t use AI to write his books, just other people—but what about Stephen King? He would certainly bristle at the term—his infamous back and forth with Shirley Hazzard at the the 2003 National Book Awards seems to indicate some sensitivity over his status—but that was how he was viewed early in his career as he cranked out potboilers by the dozen. Yet King, bolstered by the populist turn in criticism, has aged into a kind of elder statesman of American fiction, and unlike many of his rivals he seems to genuinely care about the craft (to say nothing of supporting and boosting young writers, which he does regularly). Still, even his biggest fans would have to acknowledge that there is a little bit of hack in him—less than half, more than a quarter. It’s a part of his appeal. So maybe hack is better understood not as a firm category but as a quality possessed in differing proportions, a measure of the degree to which the desire for commercial success outweighs the concern for artistry. Most writers have a a little bit of hack in our hearts, lodged there like shrapnel. We all gotta eat.

If you’re a pure hack chances are you’re already using AI. For the Amazon turn-and-burns, the disinterested copywriters whose only aim is maximizing their SEO, the college students churning out essays for courses they resent being made to take, the tech is already up to the task. A hack is already generic, by design, because being anything else takes time and time is the hack’s true enemy, time and its everpresent henchman, effort. For writers who make their living eluding those two AI is unavoidable—either learn to incorporate it or be replaced. New technology doesn’t come for professions, it comes for skill sets. Word processing software replaced typing, not secretaries. For now publishing houses are adamant that they do not want books written with AI assistance—in part because of the very real risk of plagiarism—but that stance could easily shift if the technology continues to improve. If you’re a commercial author with a big five contract to write a book a year and you’re, say, seventy percent hack, the pressure to offload some of that work load onto a piece of software will be immense. The stigma may fade.

As for the other end of the scale, the writers whose work seems blissfully unconcerned with commercial viability? The New York Times recently released its list of best books of the 21st century so far and they run the length of genres, including some—science fiction, crime, fantasy—that were once considered the sole province of hacks. There’s been plenty of debate over the ranking of various authors (or exclusion: ahem, DeLillo anyone? Pynchon?!?) but the fiction represented by the list—regardless of genre—is united in being, to a high degree, literary. That is, it takes the craft of its own making seriously and engages with the world in thoughtful, complex ways. There are tensions, inconsistencies, they aren’t machined down into approximations of what good writing sounds like. They bear the mark of human touch. They have qualities that can only be produced by the friction between a living mind and a blank page.

Of course those books have commercial appeal as well, to differing degrees. Elena Ferrante is a global sensation, and many of the others are rich and, in some circles at least, famous. As alway, matters of class confound matters of taste. But none are in any danger of being replaced by ChatGPT, and any attempt to use it to make their process easier or quicker would only diminish the final work. It’s almost as if AI were a tool for another industry, equipment for a different sport.

This isn’t meant to be an endorsement of snobbery. Like everyone else I have my opinions of what makes for good writing, but that isn’t what’s at issue here. I love plenty of hacks and plenty of literary fiction and plenty of writers along the deep spectrum that runs between the two, the swirling mixture that is the unfortunate reality of making art in a capitalist age. Most of us want readers, and want to be generous to them—but most of us would also like to challenge them, and upset them, maybe even ruin an afternoon or two, payback for all the times our afternoons have been so exquisitely ruined by writers we love—with deaths and misfortunes, with characters who seduce you only to disappoint, with ideas about the world that seem so new, so fresh, that they can only be felt as destruction.

This, in the end, is why I’m confident about the future of fiction. Good writing requires more than the synthesis and recombination of data; like the mind, it transcends its parts. Literature can’t be spat out by a search engine. In the future, researchers may approach the problem of AI from a different path, one that perhaps holds more promise and more threat. But for now, the only stories the machines can tell us are the ones we already know.

.

Great synopsis of artificial intelligence vs. actual intelligence. I totally agree A.I. will never replicate the

human mind, especially in creating original art of any kind, or be a threat to humans. You did a super job explaining it and clarifying the capabilities of A.I.!